Shorta – Glasgow Film Festival Review

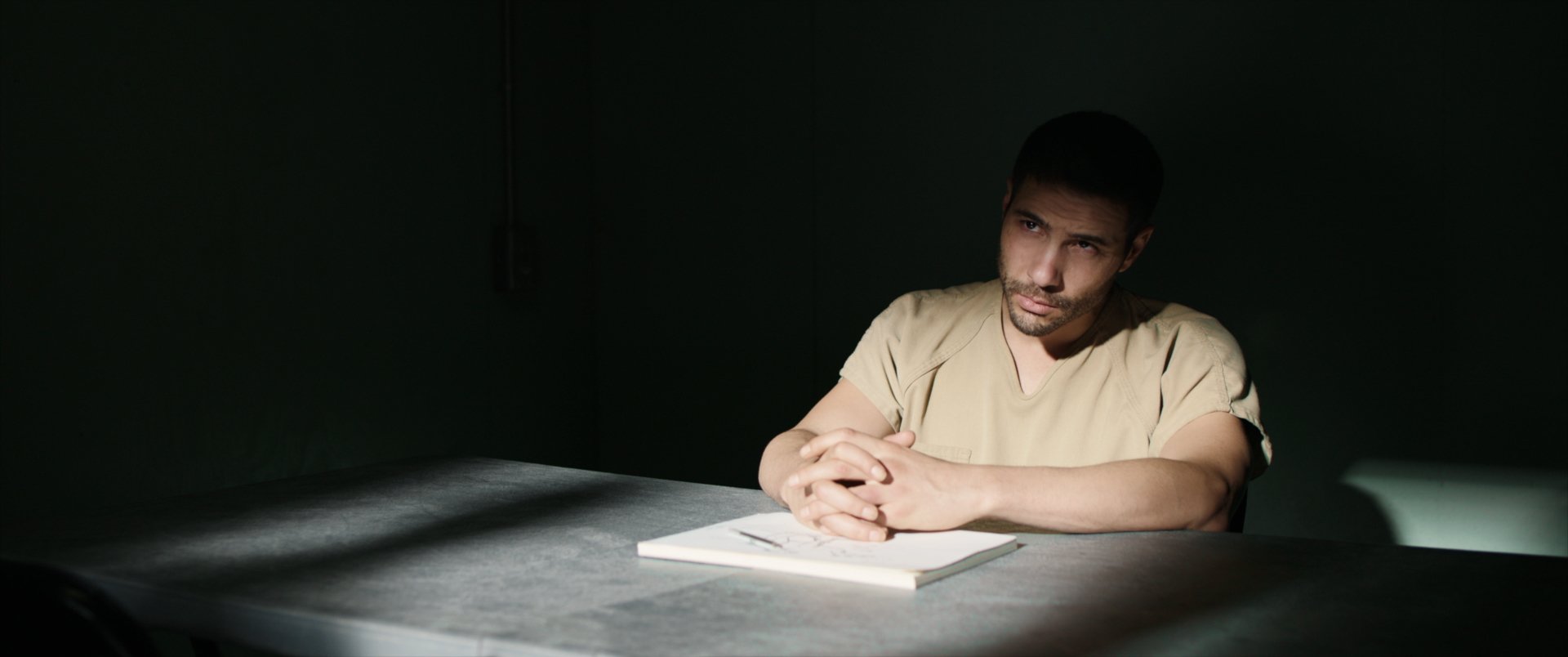

Young Arabic immigrant Talib Ben Hassi (Jack Pedersen) lies in critical condition in the hospital after a violent encounter with the Copenhagen police. His community are fed up with being a target of the people who are meant to protect them, and are anxious for further news. Meanwhile, cop Jens Hoyer (Simon Sears) is partnered for the day with Mike Andersen (Jacob Hauberg Lohmann), notorious around the station for his bigotry and combustible temper. When news of Hassi’s death is released, Hoyer and Andersen get trapped in the Svalegarden ghetto, populated solely by people who have had enough of police persecution and are determined to fight back. The stage is set for massive bloodshed; will Hoyer and Andersen make it out alive?

Shorta (an Arabic term for the police) is certainly timely – it’s no coincidence that almost the very first words we hear are Hassi’s: “I can’t breathe!” For the best part of an hour, the movie does a solid job of interrogating some of the many issues around police brutality towards racial minorities, and the self-protecting atmosphere that lets the perpetrators get away with it. Although from the beginning, Hoyer is set up as the ‘good cop’ and Andersen as the ‘bad cop’, Shorta explores how Hoyer’s silence as he witnesses Andersen’s egregious misdeeds makes him complicit. He looks deeply uncomfortable, but he never attempts to stop him; even when Andersen tries to provoke a reaction after doing something awful, (“Got anything to say?”), Hoyer is silent. The film is at its most interesting when it explores this uneasy dynamic, and illustrates how personally refraining from engaging in racist brutality isn’t enough when you have the power to stop it.

Things go off the rails when Shorta separates the two cops. Early on, they arrest Amos (Tarek Zayat), who has thrown a milkshake at their car in revenge for Andersen’s purposeful humiliation of him. As the riot heats up, Amos is stuck with them. In the midst of a burst of violence, the three get split up: Hoyer tries to take Amos home, whilst Andersen tries to find them. A wounded Andersen is taken in and protected by Amos’s mother Abia (Özlem Saglanmak), which precipitates a cloyingly cheesy sequence where – to a swelling musical score, no less – he discovers that the immigrants he’s been hating are people too. With hopes and dreams and everything! Shorta hasn’t exactly been subtle up to that point, but the heavy-handedness of this realisation is so clumsy, it takes the viewer right out of the movie, and there’s nothing in the remainder of the time to win them back. Andersen finds himself in a lift with a rabid dog, yet the scene is shot in a way that very much suggests that man and dog were never within 50 feet of each other. A concluding twist again aims to upend the traditional good cop/bad cop dynamic, but the film has already covered the same ground with far more fleetness of foot in the opening act.

The performances are impressive, the first hour is strong, and it would be hard to accuse the movie of being ‘copaganda’. What a shame then, that Shorta just doesn’t stick the landing.

★★★