Live Music Review: Bon Iver at the Hammersmith Apollo

If you walk through the Tate Britain from beginning to end, you can watch the West’s conception of beauty change through the ages. In 1850, beauty was divine: gorgeous landscapes, meticulous city views and hazy portraits of heavenly figures. Then the wars came, and from 1914 our aesthetic was torn and twisted. We were horrified and fascinated by the understanding that evil is a mundanity rather than an aberration. Representation and unity gave way to abstraction and deconstruction, edging beyond the picture frame into installations, performances and anguished films. The 1990s room is a nuclear-haunted scream. How do you figure beauty in a world where we know Hiroshima and Auschwitz to be possible? How do you sing when God seems to have disappeared over the horizon?

I mention this because Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon does much to reconcile that conflict in his weird, gorgeous music. Songs like ’33 “GOD”’ and ‘715 – CRSSKS’ teeter gracefully on the border between harmony and chaos, fitfully dancing between angry pain and sweet softness. Like the painters of 1850, Bon Iver make art with a pristine beauty that points to something bigger than the evil that men do. But that evil is ever-present in the lyrics and the tortured melody lines, barking and snapping at each structure as it arises. The songs are so close to recognisable pop tropes, and yet so fragmented, so febrile. You’re aware that somewhere a virtuoso kind of control is pulling the strings with a purpose, but you can never fully trust it. The music is spellbinding but always just on the brink of falling apart. Tonight at the Hammersmith Apollo, that productive tension is given full flight on stage. Bon Iver’s performance is huge and delicate, impenetrable and enthralling. The show begins with the one-two salvo of ‘Heavenly Father’ and ’10 d E A T h b R E a s T’, the warm vocal stylings of the former giving way to the latter’s thundering dub thump, lulling us down before detonating a musical bomb. The bass is simply earth shattering, shaking our bodies from hair to boots. It’s quite an experience to be thrummed like a guitar string, and after the melismatic opener, it’s the sonic equivalent of a horse kick to the chest.

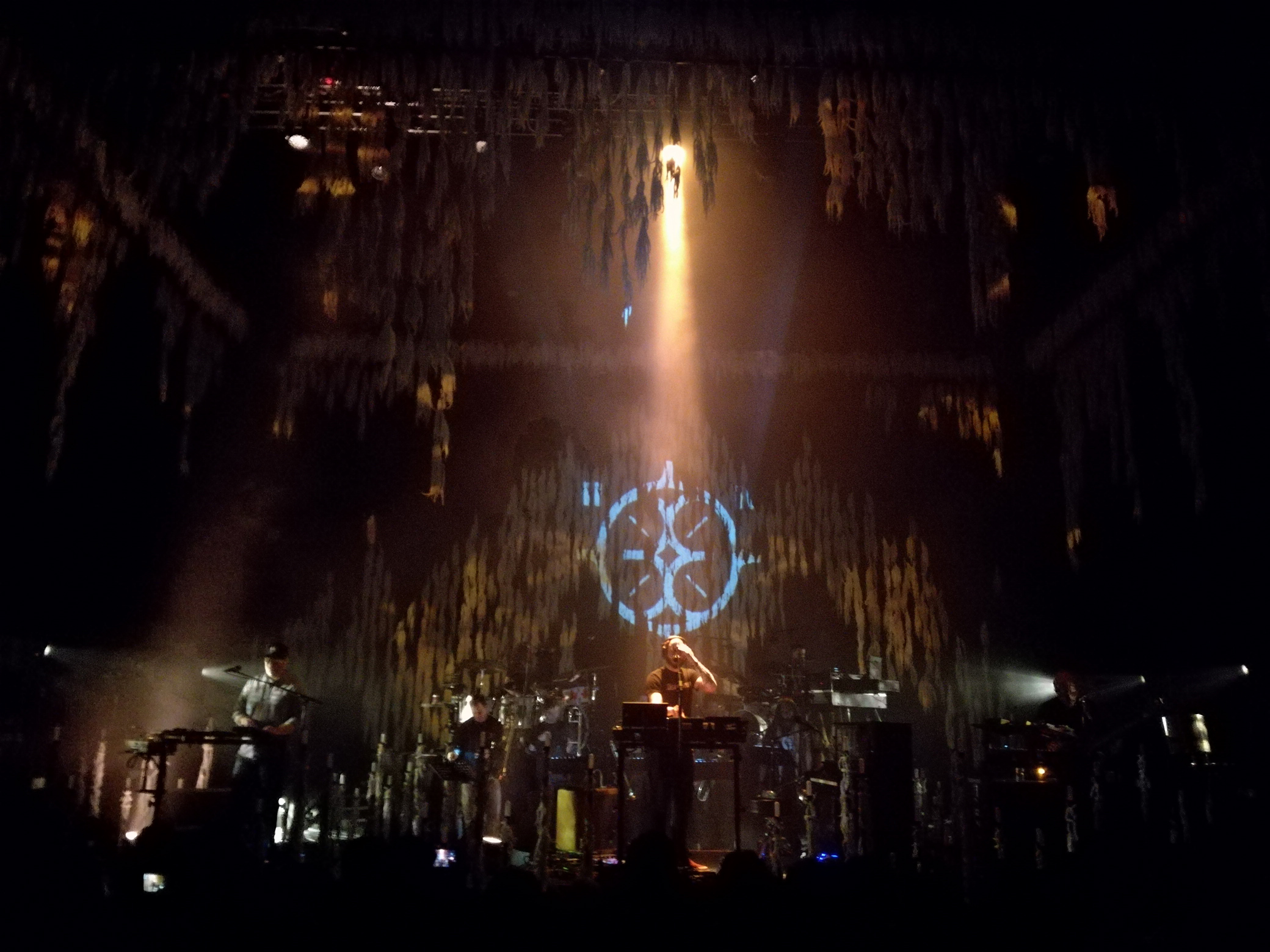

Tonight at the Hammersmith Apollo, that productive tension is given full flight on stage. Bon Iver’s performance is huge and delicate, impenetrable and enthralling. The show begins with the one-two salvo of ‘Heavenly Father’ and ’10 d E A T h b R E a s T’, the warm vocal stylings of the former giving way to the latter’s thundering dub thump, lulling us down before detonating a musical bomb. The bass is simply earth shattering, shaking our bodies from hair to boots. It’s quite an experience to be thrummed like a guitar string, and after the melismatic opener, it’s the sonic equivalent of a horse kick to the chest.

Vernon stands front and centre behind a bank of screens, keyboards and guitars, a pair of over-ear headphones clamped onto his head, Roger Waters style. He has the air of a mad scientist, underlit and swaying, the fulcrum of this flickering aural mass. His voice is impressively varied, handling warm baritone and shimmering falsetto with equal ease. He is a bear of a man, and during his inter-song chat, easy-going and humorous. He’s the kind of person who’d spend three days drinking beer and playing video games, and then go and write the Flight of the Bumblebee. Technology and acoustic instruments are put to work closely in tandem tonight, and Bon Iver use the new and the old to whip up a storm of mysterious, wistful sounds, occasionally breaking into free-jazz noise breaks or settling down into easy, rolling folk. The skill on display is staggering – at one point Vernon vocodes an entire saxophone solo, the two musicians reeling off notes in perfect unison, giving off a noise that wouldn’t sound out of place at the launch of a planet-sized spaceship. The crowd are silent – we are here to listen, and we’re well rewarded.

Technology and acoustic instruments are put to work closely in tandem tonight, and Bon Iver use the new and the old to whip up a storm of mysterious, wistful sounds, occasionally breaking into free-jazz noise breaks or settling down into easy, rolling folk. The skill on display is staggering – at one point Vernon vocodes an entire saxophone solo, the two musicians reeling off notes in perfect unison, giving off a noise that wouldn’t sound out of place at the launch of a planet-sized spaceship. The crowd are silent – we are here to listen, and we’re well rewarded.

This is what happens when genius is diverted into popular styles. Justin Vernon may write with vocoder and looper in mind rather than orchestra, but the complexity and maturity of his music should in time see it bracketed with the great works of composers like Shostakovich and Dvorak. This show was a masterpiece of enigma and dark beauty, a shuddering example of how harmony and discord can find a common purpose in modern music. Quite magical.

SaveSave