Author Q&A: Cynthia So discusses the Proud anthology, her short story The Phoenix’s Fault, LGBTQ+ diversity and Asian culture in literature

Proud is a collection of stories and artworks from various creatives, all on the theme of Proud and what it means for the LGBTQ+ people who have contributed to the collection. You can read more about the Proud collection in our review.

Here, I interviewed one of the rising star voices who contributed to the collection, Cynthia So, whose story The Phoenix’s Fault imagines a world where dragons and phoenixes are the living symbols of a heterosexual male and female union, looking at what it means when someone considers straying from this norm.

We discuss what Proud means to her, what creative works she’s loving right now, how asian culture is portrayed in media and whether we might get more stories from this world.

Nick Gomez: What was the inspiration for your Proud story, The Phoenix’s Fault?

Cynthia So: I saw the phoenix and the dragon a lot growing up—pictures of them, that is! They do in fact symbolise heterosexual marriage in Chinese culture, just as they do in my story, so every big Chinese restaurant in Hong Kong tends to have a wall that features a phoenix and a dragon, which is used as the backdrop for wedding banquets, and a lot of my anxiety around the heteronormative expectations of Chinese society is inextricably tangled up with this symbol.

When I was a teenager, I wrote a poem entitled “defying tradition” that ends “I will stand as a traitor, / not in between the phoenix and the dragon, / but next to a woman who, / like me, / seeks a phoenix to match her own”. Since then I’d always had the thought in the back of my mind that it would be interesting to return to that idea and explore it literally. I wanted to write about a world where phoenixes and dragons are real, and about a girl with a phoenix that doesn’t want a dragon. And I finally did, with The Phoenix’s Fault.

NG: One of my takeaways from the story is about the power of visibility, with the girl at the end seeing Chilli Oil and her phoenix, and Jingzhi and Xiayin together. How does visibility intersect, or not, with your identities?

CS: Oh, I have a lot of emotions about the power of visibility and I’m so glad that this was one of your takeaways from the story. Queerness was invisible to me as a child. In my experience, coming from a fairly conservative Chinese family, it’s just not something people talk about at all, and it’s hardly ever shown in media. I wasn’t aware that gay people existed until I was eleven and stumbled upon m/m fanfiction.

In the same year I started boarding school in England and also realised that I myself am queer. And I was so happy to see that there was actually some LGBTQ visibility on TV here. But what I didn’t really think about at the time was that the LGBTQ representation in media was pretty much all white.

Even though I experienced both racism and homophobia as I was growing up in England, I grappled with my queerness much more—because it wasn’t visible to others, and I didn’t really know any out queer people in real life, whereas I had several Chinese friends. The questions of whether I should come out, who I should come out to, how I should come out—I struggled with these constantly. I didn’t have to think endlessly about telling people I’m not white, so the fact of my being Chinese didn’t seem as important to me.

But I’ve come to see that being both Chinese and queer impacts me in a way that just being queer or just being Chinese doesn’t. I’ve had trouble feeling like I belong in Chinese spaces because I’m queer, and I sometimes feel invisible in queer spaces because I’m Chinese. There’s a pop singer from Hong Kong called Denise Ho who is the first out queer female star there. She came out when I was eighteen. That was such a huge and powerful moment for me: to finally see someone who is so visible and from the same place as me be both.

NG: Do you feel represented in books, films, and other media? If so, which ones?

CS: For me to feel truly represented in something I think it needs to have at least one queer female character of colour. More and more I’m finding excellent representation that makes me feel seen, and it’s a really wonderful feeling.

Black Sails, a pirate-y prequel to Treasure Island which starts off with lots of nudity and explosions before you realise it’s actually easing you into a super thoughtful and complex story about imperialism and marginalisation and narrative and history, with several great queer characters including a black lesbian.

The Netflix reboot of One Day at a Time, a heartwarming comedy that makes me cry nearly every episode, about a Cuban-American family including a teenage lesbian daughter.

Steven Universe, a cartoon about a family of aliens (all voiced by women of colour!) formed from magical gemstones and a young half-alien boy protecting Earth from harm, which is so delightfully queer in every way.

Saving Face is such a wonderful lesbian romcom about two Chinese-American women in New York, and it’s the first thing I ever saw with queer Asians in it.

I loved Legend of Korra. It was such an emotional and affirming moment when Korra and Asami ended up together—and it was something I never believed I could have even though I’d wanted it. I really didn’t think that could ever happen, but it did, and it felt so validating. These two female characters, who have each been in romantic relationships with male characters through the series, can walk off into the sunset/glowing portal to the spirit world together. Queer Asian women can exist even in children’s cartoons. I’m still getting choked up just thinking about it now, and it’s been years.

Lastly, the most mainstream and popular piece of media that features a queer East Asian female main character is probably Killing Eve. I cannot begin to put into words how it felt when I first saw a promo for Killing Eve on the side of a bus last year. I would hear people at work talking about the show and it was so amazing to finally feel represented in something that so many people have seen.

NG: How do you feel about how Chinese culture is represented elsewhere in literature? Are we hearing enough from Asian voices in general in creative works?

CS: My feelings about this are complicated. I must admit I haven’t read a great deal of literature that represents Chinese culture, because I tend to feel alienated from it by virtue of my queerness. These days I don’t really tend to read much stuff that doesn’t have some kind of queer rep, and I think I would feel worse reading a book about Chinese characters that doesn’t have any queer rep than I would reading a book about characters of any other ethnicity that doesn’t have any queer rep—because it would make me feel more keenly like an outsider to a culture that I’m supposed to belong to.

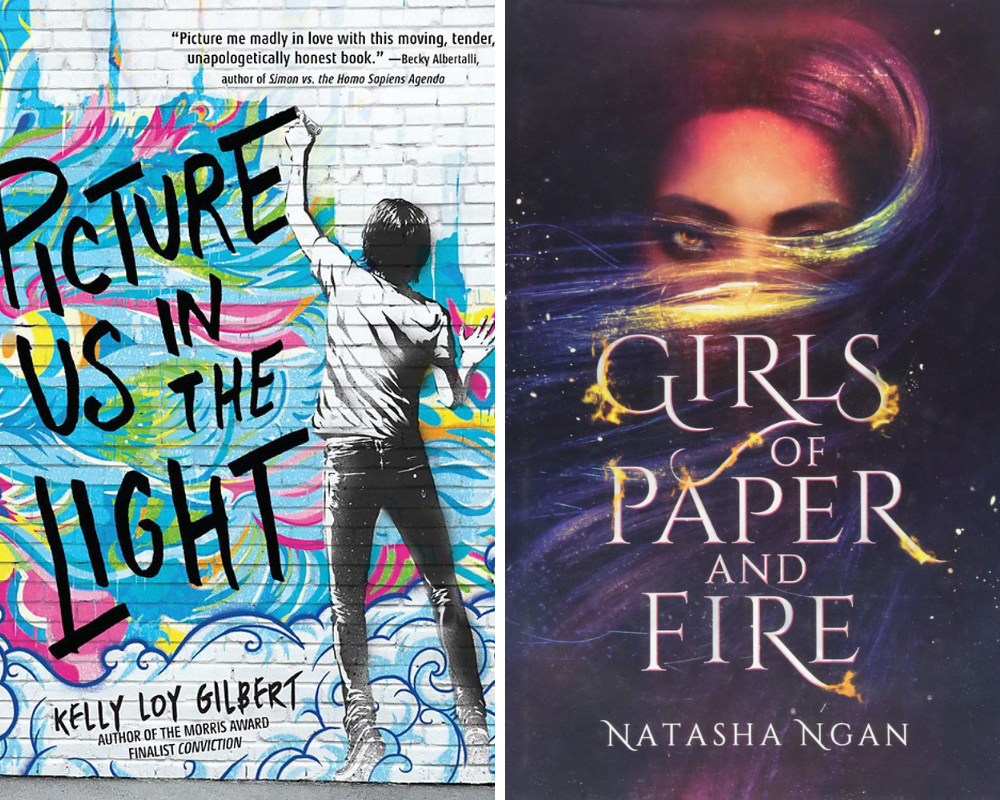

Last year I read Picture Us in the Light by Kelly Loy Gilbert, a contemporary YA book about a gay Chinese-American boy. His family is a huge part of the book, and the way the book depicts that family felt so true to me. And I loved Girls of Paper and Fire by Natasha Ngan, who drew on her Chinese Malaysian background to create the world in her story. It was breathtaking to see elements that I recognise from all the Chinese stories I enjoyed as a child combined with this really powerful love story between the two main female characters. So I would really like to see more stories like these, where Chinese culture and queerness can coexist. I definitely think we aren’t hearing enough from Asian voices in general in creative works, especially here in the UK. I’m seeing much more Asian rep in TV shows and movies produced in the US, and I’d love to see more here.

I definitely think we aren’t hearing enough from Asian voices in general in creative works, especially here in the UK. I’m seeing much more Asian rep in TV shows and movies produced in the US, and I’d love to see more here.

NG: It was nice to see Jingzhi getting a positive response from her mother in regards to her attraction to Xiayin. Was this similar to your own experience?

CS: My mother’s reaction to my bisexuality has been… mixed, but on the whole I’d say that it’s been more positive than negative. Where my experience notably differs from Jingzhi’s is that her mother seems sure that the grandparents will be okay with it. My mum was adamant that I shouldn’t tell my grandparents. And I’m fine with that.

Personally, my mum is the only person in my family I’ve ever really felt the need to come out to. To me as an Asian person, family is important in a different way than to people in other cultures, and I believe that not being out to most of my family doesn’t mean I’m not proud. I have to state this because I’ve actually heard a white person say that if you’re not out to everyone, that means you’re ashamed. But I think it’s so much more complex than that. You’re valid if you choose not to come out to your family for whatever reason.

NG: Would you want to write more stories in the world you created in The Phoenix’s Fault, perhaps continuing the story?

CS: I don’t have any plans to continue the story at this moment—though this could change in the future!—but if you’re looking for more stories set in the same world, I wrote a story called The Poet and the Spider with more queer girls and mythical creatures in fantasy China. There aren’t any explicit links to The Phoenix’s Fault, but I like to think that the events of the two stories take place in the same world, maybe half a century apart. And I would really love to write more queer fairy tales in the same vein.

NG: Which of the other pieces in Proud, stories or pieces of art, did you most enjoy?

CS: Honestly I was blown away by the quality of every single piece in Proud. I was excited to be a part of it, of course, but when I read the whole anthology, I genuinely loved it so much from the first page to the last and it made me feel even more overjoyed that I could be a part of something so special.

But if I had to pick, the pieces that spoke to me the most were probably On the Run by Kay Staples and Love Poems to the City by Moïra Fowley-Doyle; plus their accompanying illustrations are so lovely and really capture the mood and essence of their stories perfectly. I’m always saying that I want more stories where queer characters are allowed to be uncertain and take their time figuring out who they are and On the Run is a perfect example of that and such a gorgeous and quiet love story to boot. And I absolutely adore stories which make great use of a city as a setting and almost as a character, and Love Poems to the City does that beautifully and with such dreamy, lyrical prose.

I’d also like to shout-out to Priyanka Meenakshi for creating such a powerful and striking illustration for my story! NG: What does being Proud mean to you?

NG: What does being Proud mean to you?

CS: I think it’s recognising your history—all the people like you who have come before you and made what you have possible. It’s embracing your individuality, appreciating that the person you are right now is valid and enough and you bring something unique to the world by being yourself, but at the same time understanding your potential and capacity to change and evolve and learn, to become a better version of yourself and to make a difference, whether it’s just to the life of somebody close to you, or something with a wider effect.

NG: What YA books are you reading right now, or have recently enjoyed?

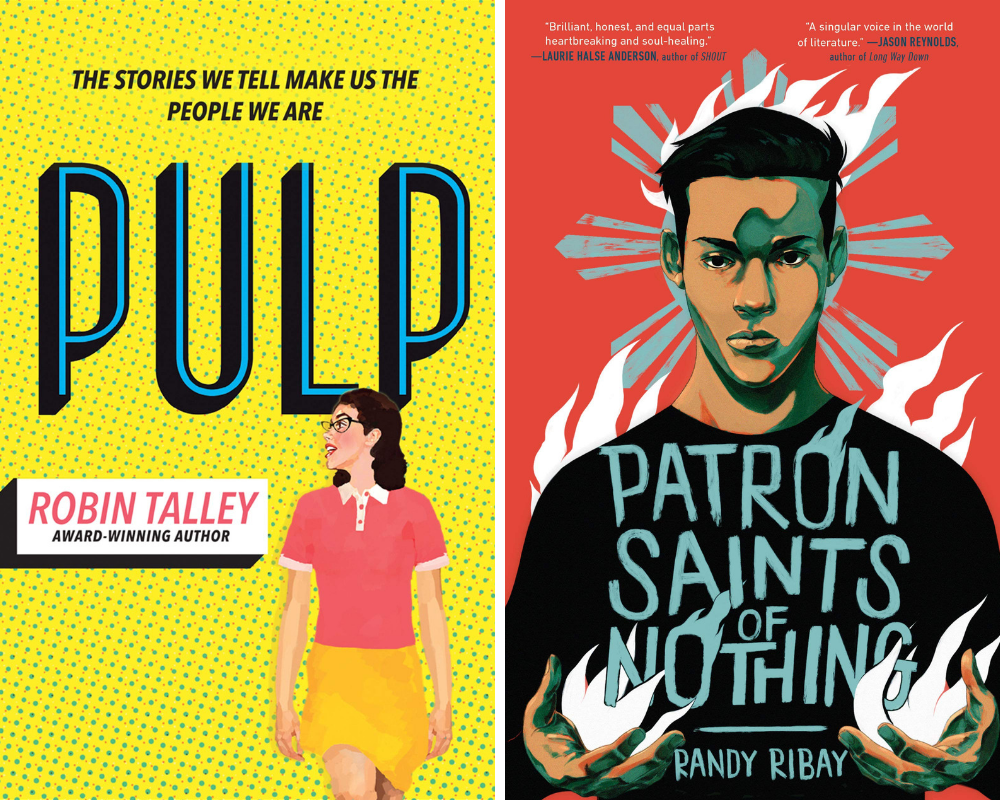

CS: I loved Pulp by Robin Talley. I’m usually a fan of stories that interweave the past and the present, and this was no exception. The juxtaposition of the relatable problems of a queer teenager in a modern environment where she can be safely out against the secrecy and fear that shrouded the characters in the past worked well. I learnt more about US history in the 1950s and lesbian pulp fiction, and I was delighted by the sheer number of queer characters in this book; there’s real diversity in the breadth of its queer rep.

I also recently enjoyed an advanced copy of Patron Saints of Nothing by Randy Ribay, a gripping story about a Filipino-American teen who goes to the Philippines to find out the truth about his cousin’s death, and it deals with President Duterte’s war on drugs. It seemed to me like it would be such a difficult topic to tackle but I thought that it was done really well, with nuance and sensitivity, and the writing was beautiful. NG: What is your earliest memory related to creative writing? Have you always been a writer?

NG: What is your earliest memory related to creative writing? Have you always been a writer?

CS: I’ve always loved writing. When I was in primary school in Hong Kong, we used to have a class called “Composition” where we would be given a prompt each week to write about for the duration of the class (about half an hour).

I remember the required word count was only 100 words but I frequently wrote around 300-500 words—which seemed like a lot back then! But I was also told off because I apparently didn’t stick to the prompts well enough—one week the prompt was “describe a storm”, but my story was about the aftermath of a sandstorm and a battered and dehydrated adventurer crawling through the desert searching for an oasis and/or treasure, so my teacher wasn’t happy that I didn’t focus on the storm itself. I was so indignant because I felt like I’d written a really good story!

NG: Finally, if you were to be transported to a fantastical world, which one would you want to go to?

CS: Oh, this is so hard! I grew up in the 90s and the first English novel I ever read on my own was a Harry Potter book. It was the first fantasy world I ever fell in love with and I’m still so fond of it. But I think maybe I have to go with the world in Avatar: the Last Airbender and Legend of Korra. Like, there are canonically queer Asian women in it, and it’s a wonderful world filled with so much beauty and magic and fun. I know it’s a world where I can feel like I belong, where I can myself and be happy, and I’ve got to say: there really aren’t many fantasy worlds out there where I would fit in even half as well.