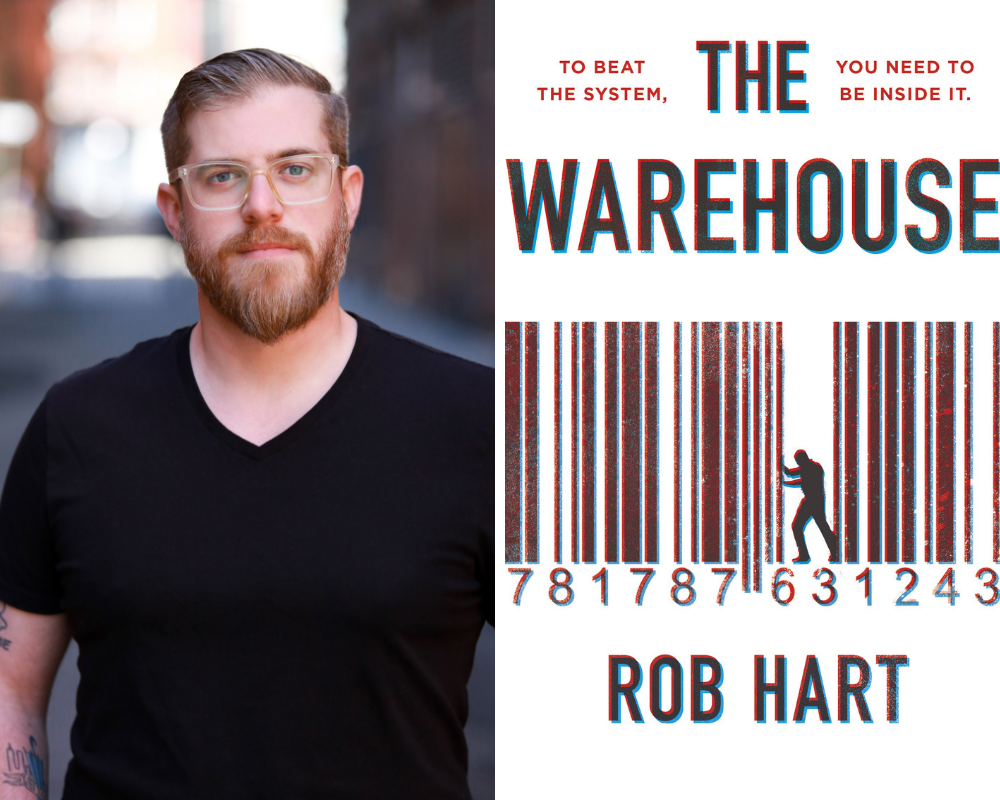

The Warehouse author Rob Hart on living inside the economic empathy gap

Rob Hart’s first standalone novel examines our day-to-day complicity in a system that prioritises cheap consumerism, conveniences and security over people’s lives. With The Warehouse hitting shelves on 13 August, Rob discusses the economic empathy gap and why his reason for writing the book is so important.

Imagine standing for up to ten hours a day, six days a week, in a sweltering workshop, cutting metal on equipment you haven’t been properly trained to use. The rubber gloves meant to protect you from caustic fluids become corroded and rarely last a full shift. The machinery is so loud it gives you a headache, but your employers don’t always provide earplugs. They do hand out carbon face masks to protect against the noxious dust and fumes—but those masks clog up quickly. The more effective, heavy-duty masks only come out when inspectors visit.

Those are some of the conditions described in reports at a Catcher Technology complex in the Chinese city of Suqian, where iPhones casings are manufactured.

This is not a new story, nor is it hard to find. Just google “iPhone factory conditions” and you’ll get a ton of hits about companies like Catcher and Foxconn, and the miserable conditions workers suffer through to provide the shiny pocket computers we line up for once a year.

There are a lot of problems here, starting with the conditions themselves, running all the way down to Apple’s continued insistence they have labor standards and companies like Catcher meet those standards.

But the bigger problem is: I think we all know the truth about our iPhones. Even if we can’t cite specifics, we know our gadgets are manufactured under conditions that would be unacceptable, if not outright illegal, in the United States.

It’s easy to ignore the poor villager whose head hurts and whose feet ache and whose lungs are filling with noxious fumes. China is very far away, and at least he has a job. Plus, we’ve got our iPhones!

This is the economic empathy gap.

Empathy gaps aren’t a new concept. It’s a cognitive bias, for which there are many studies and examples. Among them: a 2014 study in PLOS One showed it’s harder to empathize with negative emotions (someone suffered to make me this iPhone) when you’re happy (I can play Candy Crush on the subway).

The gap reaches far beyond our gadgets. Look up “poultry workers bathroom breaks.” You’ll find the Oxfam report about the processing plant workers who wear diapers because they’re denied bathroom breaks. Look up “conditions in fulfillment centers”—you might come across the story of Erica Hayes, a pregnant woman working in a Verizon shipping facility who, after she found out she was pregnant, begged her supervisors to let her work with lighter boxes. They said no, and she miscarried.

At this point, you might feel like you’re being lectured.

Which is fair.

But it’s also fair to say that I’m no better.

I’ve got an iPhone. I eat chicken. I’m writing this on Verizon wifi.

I live inside the economic empathy gap too.

Because it’s easy. But also because it’s hard to find any kind of ethical consumption under capitalism. I shop at a local market I can walk to, that employs people who live in my community. But when I buy fresh vegetables from them—what kind of wage was paid to the laborer who picked it? What was the carbon footprint of getting it there?

Therein lies the problem: these systems we’ve built and bought into are so big, they’re dug so deeply into our day-to-day lives, that we can’t just snap them away.

That empathy gap is why I wanted to write The Warehouse. The book imagines a world where one large company completely dominates the retail economy, then builds dormitory housing for its workers, so no one ever has to leave their job. It is, chiefly, about the way corporations treat us like disposable products. But more than that, it’s about how we’ve decided our own comfort is worth someone else’s discomfort.

Which, many days, I fear is a problem without a solution.

Or at least: a clear, definitive solution.

And I’m not going to pretend like this book has answers. But if it can start some conversations, that wouldn’t be so bad. Because maybe the first step is being more cognizant of who served us our coffee, or who cut the casing for the device we’re reading this on. We can think about their aching feet or their scratchy lungs, and the comfort those things gave to us—and what the real cost of those items were.

The Warehouse is published by Bantam Press on 13 August 2019