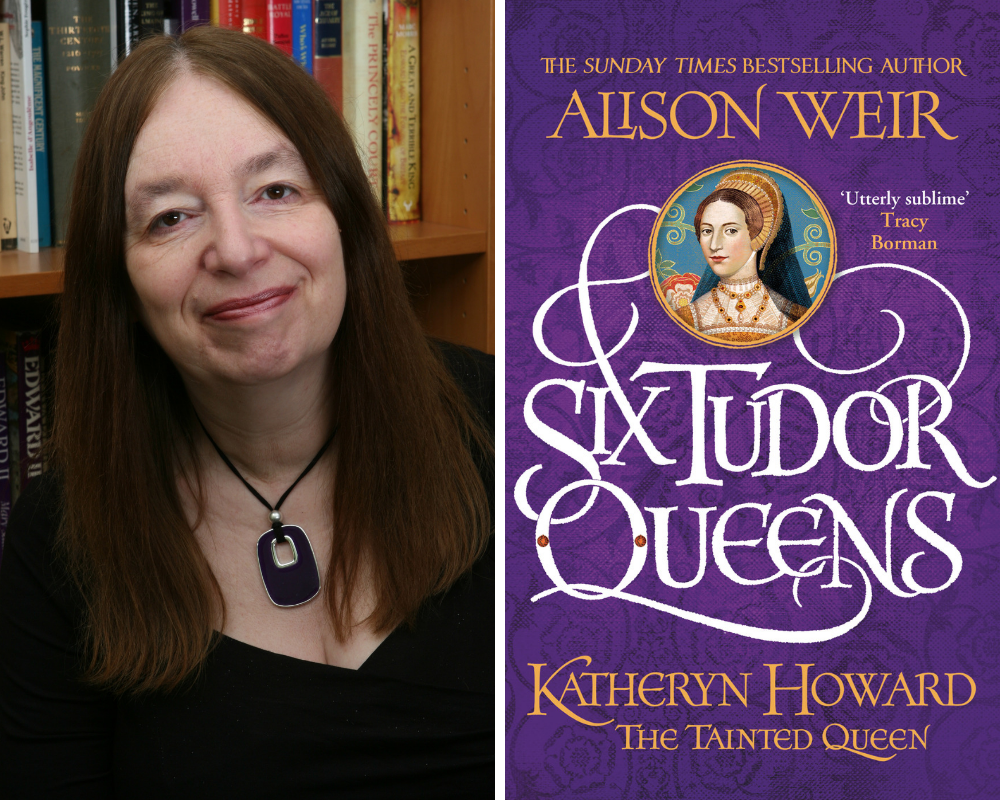

Alison Weir: Ramping up the proclamations – how Henry VIII dealt with epidemics

Forget one metre. Henry VIII’s idea of social distancing was seven miles. When he married his fifth wife, Katheryn Howard, in the hot, dry summer of 1540, there was plague in London, which claimed many lives.

Tudor England did not have to cope with coronavirus, but it often faced comparable threats. There were outbreaks of plague most summers, for it spread rapidly in hot, crowded, dirty conditions, and London, which had about seventy thousand inhabitants crammed inside its walls, was invariably the worst-afflicted place. In 1513, 300-400 a day died of plague in the capital, mainly poor people, who had not the means to escape the pest, as their betters could. There was plague and ‘great death’ in the capital in 1543, when a proclamation forbade Londoners from coming within seven miles of the King.

There were also epidemics of the sweating sickness, a terrifying disease that could kill with devastating speed. In 1517, Sir Thomas More wrote: ‘Multitudes are dying around us.’ ‘One has a little pain in the head and heart; suddenly, a sweat breaks out, and a physician is useless, for in four hours – sometimes within two or three – you are despatched without languishing.’ A man could be ‘merry at dinner and dead at supper’. One rumour might cause ‘a thousand cases of sweat’, for people ‘suffered more from fear than others did from the sweat itself’. In 1528, there was a particularly virulent outbreak, with forty thousand cases in London alone.

Henry VIII was morbidly terrified of disease, especially the plague, being ‘the most timid person in such matters you could meet with’. The mere words ‘sweating sickness’ were ‘so terrible to His Highness’s ears’ that he kept constantly on the move to escape contagion and avoided taking baths for fear of catching ‘evil humours’. He would shut himself up with just his Queen, his physician and just three of his favourite gentlemen, attending Mass more frequently than usual and concocting his own remedy for the sweat, an infusion of sage, rue and elder leaves. Parliament was adjourned and all but the most necessary government business was held in suspension.

Plague was raging in 1537, when Henry’s longed-for son, Edward, was christened, and numbers were restricted. Henry’s fear is evident in the strict ordinances he imposed on the Prince’s household, which were designed to eliminate all risks to his son. No servant was to speak with persons suspected of having been in contact with the plague. The walls and floors of the rooms, galleries, passages, and courtyards in and around the Prince’s apartments had to be swept and scrubbed with soap thrice daily. Members of his household were to observe stringent standards of personal hygiene, and everything that might be handled by the baby had to be washed before he came into contact with it.

Sadly, Henry VIII and his subjects knew that the plague would return, without fail, in the future.

Six Tudor Queens: Katheryn Howard, The Tainted Queen is published by Headline in Hardback, eBook and Audio Digital Download on 6 August 2020